Understanding and Overcoming the Fear of Public Speaking

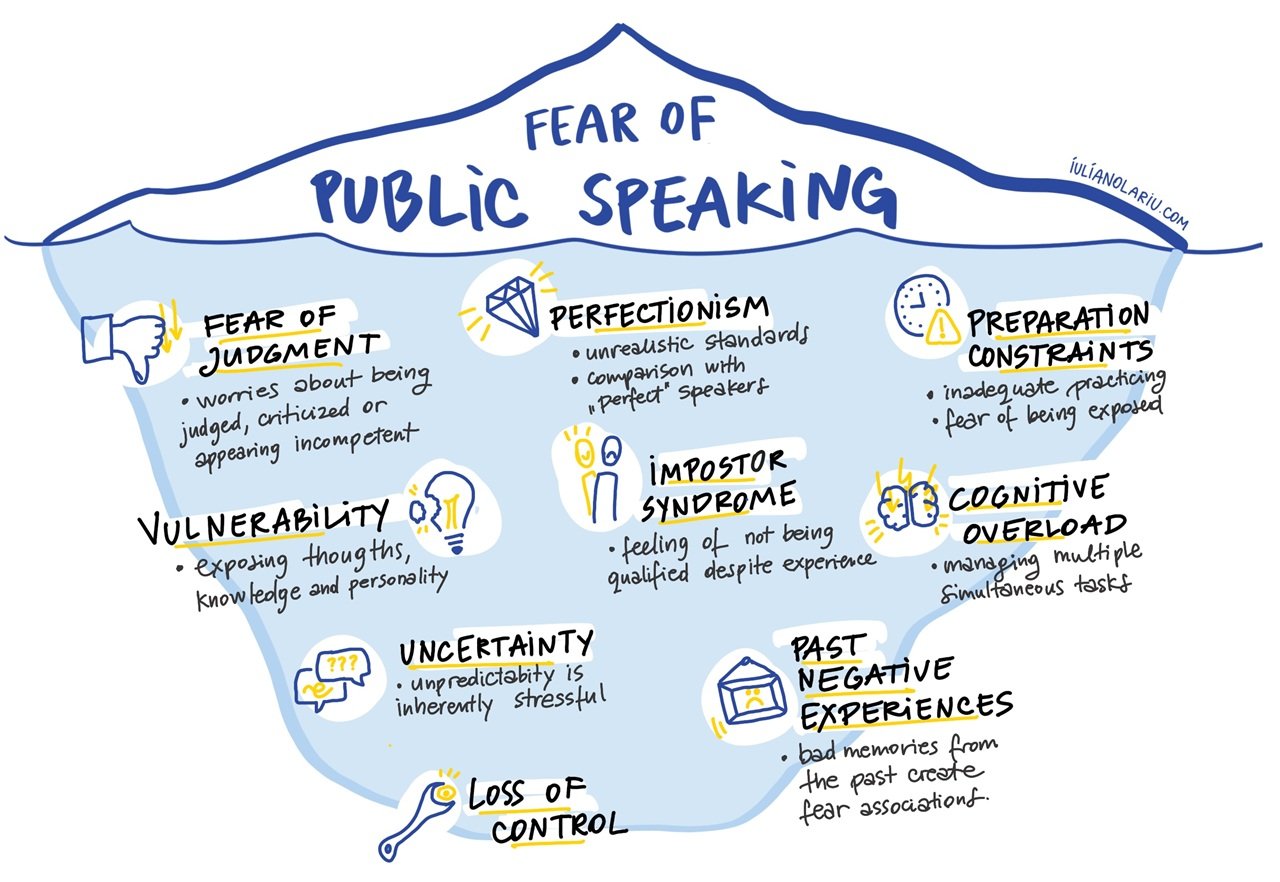

One of the topics I address in my Presentation Skills Masterclass is the psychology behind the fear of public speaking. Once you understand what’s happening beneath the surface, the stress feels less like a problem and more like a natural response you can work with. I hope this comprehensive guide will help you better overcome the stress of delivering a high impact presentation. Keep in mind that quite often confidence doesn't come from eliminating fear, but from understanding it.

This framework is one small part of my Presentation Skills Masterclass, where you'll understand these mechanisms better and learn how to speak with clarity, confidence and presence.

People get stressed before presentations for several interconnected psychological reasons. At its core, a presentation is a moment of social evaluation: dozens of eyes are on you, waiting, expecting. Your brain interprets this as a potential threat because, for most of human history, being judged by the group had real consequences. The amygdala doesn't distinguish between a room full of colleagues and a tribe deciding whether to accept you.

The good news? When we understand what's happening, we can start shifting from fear to intention. Remember: the goal isn't to eliminate nervousness entirely. Some anxiety actually enhances performance by keeping you sharp. The goal is to prevent anxiety from becoming overwhelming and to recognize that feeling nervous doesn't mean you'll perform badly.

1. Fear of Judgment and Evaluation

Your brain interprets the presentation as a potential threat. The amygdala (your brain's alarm system) reacts as if you're facing actual danger. This shows up as a racing heart, shaky hands, or a voice that feels less stable than usual.

Strategies to Overcome

Reframe the Audience's Role: Instead of viewing your audience as judges, see them as collaborators who want you to succeed. Most people are rooting for you, not against you. They're thinking about their own tasks, how your content applies to them, or other thoughts. They are not scrutinizing your every move.

Practice Exposure Gradually: Start with low-stakes presentations. You can present to a friend, then a small supportive group, then gradually larger audiences. Each positive experience rewires your brain's threat response, teaching your amygdala that presentations aren't actually dangerous.

Use Physiological Calming Techniques: Before presenting, try the breathing techniques. This activates your parasympathetic nervous system, physically calming the fight-or-flight response. Do this several times in the minutes before you present.

2. The Perfectionist Trap

Internal pressure makes the presentation feel like a measure of your competence and worth. Small mistakes suddenly feel catastrophic. The gap between how you wish to sound and how you fear you might sound creates paralysing anxiety.

Strategies to Overcome

Set Realistic Standards: Define success as "communicating my key points clearly" rather than "delivering a flawless performance." Even TED speakers stumble, pause and adjust. Perfection is neither possible nor necessary for effectiveness.

Plan for Imperfection: Prepare a "mistake recovery phrase" in advance, such as "Let me rephrase that" or "To clarify what I meant..." When you have a plan for handling errors, they become manageable moments rather than catastrophes.

Celebrate Small Wins: After each presentation, identify three things you did well before critiquing anything. This rewires your brain to associate presenting with positive outcomes rather than only noticing flaws. Keep a "wins journal" to review before future presentations.

Practice Self-Compassion: Speak to yourself as you would a good friend. Would you tell a colleague they're worthless because of a stumbled sentence? The harsh self-criticism doesn't improve performance. It only just adds suffering to an already stressful situation.

3. Preparation Constraints

Having to present with inadequate preparation time (due to work demands, competing priorities or last-minute assignments) creates a sense of helplessness and anticipated regret. Knowing you're not as prepared as you'd like but having no choice amplifies stress.

Strategies to Overcome

Focus on Core Messages: When time is limited, identify your 3 most important points. A presentation with 3 well-delivered messages beats one with 10 rushed ones. Ask yourself: "If the audience remembers only one thing, what should it be?"

Use Structured Templates: Develop a go-to presentation structure you can apply quickly: Opening hook → Problem → Solution → Evidence → Call to action. Having a reliable framework reduces cognitive load when preparation time is short.

Leverage Existing Materials: Don't start from scratch if you don't have to. Re-purpose slides, examples or content from previous presentations. Build a personal library of go-to stories, data points, and visuals you can quickly adapt.

Communicate Constraints Transparently: If appropriate, briefly acknowledge time limitations: "I had limited notice for this presentation, so I'll focus on the key findings and leave time for your questions." This manages expectations and reduces the pressure you're putting on yourself.

4. Impostor Syndrome

You believe you're a fraud despite evidence of competence, feeling you've somehow fooled others into thinking you're capable. You live in constant fear of being "found out." Paradoxically, this often intensifies with success: the higher you climb, the further you feel you have to fall.

Strategies to Overcome

Document Your Qualifications: Before presenting, write down your relevant experience, accomplishments, and expertise. Review this list when impostor feelings arise. You were invited to present for a reason: you have knowledge others need.

Normalize "Not Knowing": Prepare phrases like "That's a great question! I don't have that data with me, but I'll follow up" or "That's outside my area of expertise, but I can connect you with someone who knows." Admitting knowledge gaps actually builds credibility rather than destroying it.

Share the Origin of Your Expertise: When introducing yourself or your topic, briefly mention your learning journey: "I've spent the past five years working on this problem" or "I've interviewed 200 customers about this issue." This grounds your authority in real experience rather than claiming to be an all-knowing expert.

Collect Positive Feedback: Keep a file of compliments, thank-you notes and positive feedback from past presentations. Review these before presenting to counteract impostor thoughts with concrete evidence of your competence.

5. Loss of Control and Unpredictability

Presentations contain countless uncontrollable variables: audience reactions, unexpected questions, technical failures, your own memory. Humans crave control, and presentations offer very little of it. This uncertainty is inherently stressful.

Strategies to Overcome

Control What You Can: Arrive early to test technology, check the room layout, and familiarise yourself with the space. Bring backup materials: a printed copy of your slides, notes on your phone, key data memorised. Having contingency plans reduces anxiety about things going wrong.

Prepare for Common Disruptions: Practice presenting without slides in case technology fails. Prepare for tough questions by anticipating objections and having responses ready. Run through "what if" scenarios: "What if someone challenges my data?" "What if I lose my place?"

Use Interactive Elements: Build in moments where you ask questions or invite brief discussion. This shares control with the audience and creates natural pauses where you can regroup if needed. It also makes the presentation feel less like a high-wire act.

Embrace Flexibility as Strength: Reframe unpredictability as opportunity. When someone asks an unexpected question, say "I'm glad you brought that up" and use it to demonstrate your adaptability. The ability to handle the unexpected gracefully impresses audiences more than a flawless scripted performance.

6. Vulnerability and Exposure

Presenting requires revealing your thoughts, knowledge, and personality in a way that feels deeply exposing. You're showing how you think, what you value, how you organize information, and how you handle pressure. For people who value privacy or who have experienced criticism or ridicule in the past, this vulnerability is deeply uncomfortable.

Strategies to Overcome

Choose Strategic Vulnerability: You don't have to share everything. Decide in advance what you're comfortable revealing and what stays private. You can be authentic without being completely transparent. Share a relevant story or perspective while maintaining appropriate professional boundaries.

Frame It as Contribution, Not Exposure: Shift your mindset from "I'm exposing myself to judgement" to "I'm contributing something valuable." Your presentation is a gift of your time, expertise and perspective. Focus on what the audience will gain rather than what you're risking.

Build Connection Through Relatability: Start with a brief, humanising moment: acknowledging shared challenges, mentioning you're nervous, or using self-deprecating humour. This creates connection and reminds you that the audience is made of fellow humans, not critics lying in wait.

7. Cognitive Overload

During a presentation, you must simultaneously: recall and organise information, deliver it clearly and engagingly, monitor audience reactions and adjust accordingly, manage time, handle questions, operate technology, control your body language and voice, and manage your anxiety. This enormous cognitive load means any small disruption can push you into feeling overwhelmed and scattered.

Strategies to Overcome

Reduce Mental Tasks: Memorize your opening and closing so you don't have to think about them. Use slides as prompts rather than trying to remember everything. Write key transitions on notes. The less your brain has to actively recall, the more capacity you have for connecting with your audience.

Practice Until It's Automatic: Rehearse enough times that the flow becomes muscle memory. When the structure is automatic, your conscious mind is free to focus on delivery and adaptation rather than "What comes next?" Practice out loud, not just in your head.

Build in Mental Breaks: Design moments of reduced cognitive load into your presentation: show a video, ask the audience to discuss something in pairs, or invite a question while you drink water. These brief pauses let your brain reset.

Use External Systems: Don't rely on your brain alone. Have a printed outline nearby, set a timer you can glance at, prepare a backup slide deck on a USB drive. External systems free up mental resources and provide security if your memory falters.

8. Past Negative Experiences

If you've had a presentation go badly, blanking, receiving harsh criticism, being humiliated or witnessing someone else's traumatic experience, your brain forms a strong association between presentations and danger. This is classical conditioning: your amygdala creates a fear memory that triggers automatically. Each time you present with high anxiety, you actually reinforce this fear conditioning, even if the presentation goes fine.

Strategies to Overcome

Create New Positive Associations: Intentionally stack small, positive presentation experiences. Present in increasingly comfortable environments: first to supportive friends, then friendly colleagues, then neutral audiences. Each positive experience begins to overwrite the old fear memory.

Process the Original Experience: If a past presentation was truly traumatic, talk through it with a trusted friend, mentor, or therapist. Understanding what went wrong and gaining perspective can help your brain reclassify it from "danger" to "difficult but survivable moment."

Use Visualization to Rewire: Regularly visualize yourself presenting successfully: speaking clearly, handling questions well, feeling calm. Your brain partially treats vivid visualization like real experience, gradually building new neural pathways that associate presenting with positive outcomes.

Challenge Catastrophic Thinking: When anxiety arises, ask: "What actually happened in my worst presentation? How did my life change afterward?" Usually, the long-term consequences were minimal. Recognizing that even "bad" presentations are survivable helps deactivate the fear response.

Presentation stress is a natural response to a meaningful moment. It reflects the importance we place on our work, our identity and the relationships we want to build. The physical sensations you experience (racing heart, nervous energy) are your body preparing you to perform.

By understanding the specific sources of your presentation anxiety and applying targeted strategies, you can transform that nervous energy from a barrier into fuel. You can prepare better, breathe deeper, simplify your message, connect with the room and allow yourself to be human in front of other humans.

Start with one or two strategies that resonate most with your personal experience. Build your confidence gradually. And remember: the audience is made of people who have also felt nervous, who also want to do well, who also know what it's like to be vulnerable in front of others.

Key take aways:

✓ Presentation anxiety affects 75% of people (it's biology, not weakness)

✓ Understanding the fight-or-flight response helps you manage it

✓ Preparation and practice build confidence over time

✓ Visual aids can serve as psychological anchors

✓ Reframing anxiety as excitement changes your physiology